- Home

- Cassandra Clare

Clockwork Prince tid-2 Page 36

Clockwork Prince tid-2 Read online

Page 36

“She used it well enough to keep you away from us. That’s why you cursed us. Cursed me. Do you remember that?”

The demon chuckled. “‘All who love you will find only death. Their love will be their destruction. It may take moments, it may take years, but any who look upon you with love will die of it. And I shall begin it with her.’”

Will felt as if he were breathing fire. His whole chest burned. “Yes.”

The demon cocked its head to the side. “And you summoned me that we might reminisce about this shared event in our past?”

“I called you up, you blue-skinned bastard, to get you to take the curse off me. My sister—Ella—she died that night. I left my family to keep them safe. It’s been five years. It’s enough. Enough!”

“Do not try to engage my pity, mortal,” said Marbas. “I was twenty years tortured in that box. Perhaps you too should suffer for twenty years. Or two hundred—”

Will’s whole body tensed. Before he could fling himself toward the pentagram, Magnus said, in a calm tone, “Something about this story strikes me as odd, Marbas.”

The demon’s eyes flicked toward him. “And what is that?”

“A demon, upon being let out of a Pyxis, is usually at its weakest, having been starved for as long as it was imprisoned. Too weak to cast a curse as subtle and strong as the one you claim to have cast on Will.”

The demon hissed something in a language Will didn’t know, one of the more uncommon demon languages, not Cthonic or Purgatic. Magnus’s eyes narrowed.

“But she died,” Will said. “Marbas said my sister would die, and she did. That night.”

Magnus’s eyes were still fixed on the demon’s. Some kind of battle of wills was taking place silently, outside Will’s range of understanding. Finally Magnus said, softly, “Do you really wish to disobey me, Marbas? Do you wish to anger my father?”

Marbas spat a curse, and turned to Will. Its snout twitched. “The half-caste is correct. The curse was false. Your sister died because I struck her with my stinger.” It swished its yellowish tail back and forth, and Will remembered Ella knocked to the ground by that tail, the blade skittering from her hand. “There has never been a curse on you, Will Herondale. Not one put there by me.”

“No,” Will said softly. “No, it isn’t possible.” He felt as if a great storm were blowing through his head; he remembered Jem’s voice saying the wall is coming down, and he envisioned a great wall that had surrounded him, isolated him, for years, crumbling away into sand. He was free—and he was alone, and the icy wind cut through him like a knife. “No.” His voice had taken on a low, keening note. “Magnus . . .”

“Are you lying, Marbas?” Magnus snapped. “Do you swear on Baal that you are telling the truth?”

“I swear,” said Marbas, red eyes rolling. “What benefit would it be to me to lie?”

Will slid to his knees. His hands were locked across his stomach as if they were keeping his guts from spilling out. Five years, he thought. Five years wasted. He heard his family screaming and pounding on the doors of the Institute and himself ordering Charlotte to send them away. And they had never known why. They had lost a daughter and a son in a matter of days, and they had never known why. And the others—Henry and Charlotte and Jem—and Tessa—and the things he had done—

Jem is my great sin.

“Will is right,” said Magnus. “Marbas, you are a blue-skinned bastard. Burn and die!”

Somewhere at the edge of Will’s vision, dark red flame soared toward the ceiling; Marbas screamed, a howl of agony cut off as swiftly as it had begun. The stench of burning demon flesh filled the room. And still Will crouched on his knees, his breath sawing in and out of his lungs. Oh God, oh God, oh God.

Gentle hands touched his shoulders. “Will,” Magnus said, and there was no humor in his voice, only a surprising kindness. “Will, I am sorry.”

“Everything I’ve done,” Will said. His lungs felt as if he couldn’t get enough air. “All the lying, the pushing people away, the abandonment of my family, the unforgivable things I said to Tessa—a waste. A bloody waste, and all because of a lie I was stupid enough to believe.”

“You were twelve years old. Your sister was dead. Marbas was a cunning creature. He has fooled powerful magicians, never mind a child who had no knowledge of the Shadow World.”

Will stared down at his hands. “My whole life wrecked, destroyed . . .”

“You’re seventeen,” Magnus said. “You can’t have wrecked a life you’ve barely lived. And don’t you understand what this means, Will? You’ve spent the last five years convinced that no one could possibly love you, because if they did, they would be dead. The mere fact of their continued survival proved their indifference to you. But you were wrong. Charlotte, Henry, Jem—your family—”

Will took a deep breath, and let it out. The storm in his head was ebbing slowly.

“Tessa,” he said.

“Well.” Now there was a touch of humor to Magnus’s voice. Will realized the warlock was kneeling beside him. I am in a werewolf’s house, Will thought, with a warlock comforting me, and the ashes of a dead demon mere feet away. Who could ever have imagined? “I can give you no assurance of what Tessa feels. If you have not noticed, she is a decidedly independent girl. But you have as much a chance to win her love as any man does, Will, and isn’t that what you wanted?” He patted Will on the shoulder and withdrew his hand, standing up, a thin dark shadow looming over Will. “If it’s any consolation, from what I observed on the balcony the other night, I do believe she rather likes you.”

Magnus watched as Will made his way down the front walk of the house. Reaching the gate, he paused, his hand on the latch, as if hesitating on the threshold of the beginning of a long and difficult journey. The moon had come out from behind the clouds and shone on his thick dark hair, the pale white of his hands.

“Very curious,” said Woolsey, appearing behind Magnus in the doorway. The warm lights of the house turned Woolsey’s dark blond hair into a pale gold tangle. He looked as if he’d been sleeping. “If I didn’t know better, I’d say you were fond of that boy.”

“Know better in what sense, Woolsey?” Magnus asked, absently, still watching Will, and the light sparking off the Thames behind him.

“He’s Nephilim,” said Woolsey. “And you’ve never cared for them. How much did he pay you to summon Marbas for him?”

“Nothing,” said Magnus, and now he was not seeing anything that was there, not the river, not Will, only a wash of memories—eyes, faces, lips, receding into memory, love that he could no longer put a name to. “He did me a favor. One he doesn’t even remember.”

“He’s very pretty,” said Woolsey. “For a human.”

“He’s very broken,” said Magnus. “Like a lovely vase that someone has smashed. Only luck and skill can put it back together the way it was before.”

“Or magic.”

“I’ve done what I can,” Magnus said softly as Will pushed the latch, at last, and the gate swung open. He stepped out onto the Walk.

“He doesn’t look very happy,” Woolsey observed. “Whatever it was you did for him . . .”

“At the moment he is in shock,” said Magnus. “He has believed one thing for five years, and now he has realized that all this time he has been looking at the world through a faulty mechanism—that all the things he sacrificed in the name of what he thought was good and noble have been a waste, and that he has only hurt what he loved.”

“Good God,” said Woolsey. “Are you quite sure you’ve helped him?”

Will stepped through the gate, and it swung shut behind him. “Quite sure,” said Magnus. “It is always better to live the truth than to live a lie. And that lie would have kept him alone forever. He may have had nearly nothing for five years, but now he can have everything. A boy who looks like that . . .”

Woolsey chuckled.

“Though he had already given his heart away,” Magnus said. “Perhaps it is for the

best. What he needs now is to love and have that love returned. He has not had an easy life for one so young. I only hope she understands.”

Even from this distance Magnus could see Will take a deep breath, square his shoulders, and set off down the Walk. And—Magnus was quite sure he was not imagining it—there seemed to be almost a spring in his step.

“You cannot save every fallen bird,” said Woolsey, leaning back against the wall and crossing his arms. “Even the handsome ones.”

“One will do,” said Magnus, and, as Will was no longer within his sight, he let the front door fall shut.

Chapter 18

UNTIL I DIE

My whole life long I learn’d to love.

This hour my utmost art I prove

And speak my passion—heaven or hell?

She will not give me heaven? ’Tis well!

—Robert Browning, “One Way of Love”

“Miss. Miss!” Tessa woke slowly, Sophie shaking her shoulder. Sunlight was streaming through the windows high above. Sophie was smiling, her eyes alight. “Mrs. Branwell’s sent me to bring you back to your room. You can’t stay here forever.”

“Ugh. I wouldn’t want to!” Tessa sat up, then closed her eyes as dizziness washed through her. “You might have to help me up, Sophie,” she said in an apologetic voice. “I’m not as steady as I could be.”

“Of course, miss.” Sophie reached down and briskly helped Tessa out of the bed. Despite her slenderness, she was quite strong. She’d have to be, wouldn’t she, Tessa thought, from years of carrying heavy laundry up and down stairs, and coal from the coal scuttle to the grates. Tessa winced a bit as her feet struck the cold floor, and couldn’t help glancing over to see if Will was in his infirmary bed.

He wasn’t.

“Is Will all right?” she asked as Sophie helped her slide her feet into slippers. “I woke for a bit yesterday and saw them taking the metal out of his back. It looked dreadful.”

Sophie snorted. “Looked worse than it was, then. Mr. Herondale barely let them iratze him before he left. Off into the night to do the devil knows what.”

“Was he? I could have sworn I spoke to him last night.” They were in the corridor now, Sophie guiding Tessa with a gentle hand on her back. Images were starting to take shape in Tessa’s head. Images of Will in the moonlight, of herself telling him that nothing mattered, it was only a dream—and it had been, hadn’t it?

“You must have dreamed it, miss.” They had reached Tessa’s room, and Sophie was distracted, trying to get the doorknob turned without letting go of Tessa.

“It’s all right, Sophie. I can stand on my own.”

Sophie protested, but Tessa insisted firmly enough that Sophie soon had the door open and was stoking the fire in the grate while Tessa sank into an armchair. There was a pot of tea and a plate of sandwiches on the table beside the bed, and she helped herself to it gratefully. She no longer felt dizzy, but she did feel tired, with a weariness that was more spiritual than physical. She remembered the bitter taste of the tisane she’d drunk, and the way it had felt to be held by Will—but that had been a dream. She wondered how much else of what she’d seen last night had been a dream—Jem whispering at the foot of her bed, Jessamine sobbing into her blankets in the Silent City . . .

“I was sorry to hear about your brother, miss.” Sophie was on her knees by the fire, the rekindling flames playing over her lovely face. Her head was bent, and Tessa could not see her scar.

“You don’t have to say that, Sophie. I know it was his fault, really, about Agatha—and Thomas—”

“But he was your brother.” Sophie’s voice was firm. “Blood mourns blood.” She bent farther over the coals, and there was something about the kindness in her voice, and the way her hair curled, dark and vulnerable, against the nape of her neck, that made Tessa say:

“Sophie, I saw you with Gideon the other day.”

Sophie stiffened immediately, all over, without turning to look at Tessa. “What do you mean, miss?”

“I came back to get my necklace,” Tessa said. “My clockwork angel. For luck. And I saw you with Gideon in the corridor.” She swallowed. “He was . . . pressing your hand. Like a suitor.”

There was a long, long silence, while Sophie stared into the flickering fire. At last she said, “Are you going to tell Mrs. Branwell?”

Tessa recoiled. “What? Sophie, no! I just—wanted to warn you.”

Sophie’s voice was flat. “Warn me against what?”

“The Lightwoods . . .” Tessa swallowed. “They are not nice people. When I was at their house—with Will—I saw dreadful things, awful—”

“That’s Mr. Lightwood, not his sons!” The sharpness in Sophie’s voice made Tessa flinch. “They’re not like him!”

“How different could they be?”

Sophie stood up, the poker clattering into the fire. “You think I’m such a fool that I’d let some half-hour gentleman make a mockery of me after all I been through? After all Mrs. Branwell’s taught me? Gideon’s a good man—”

“It’s a question of upbringing, Sophie! Can you picture him going to Benedict Lightwood and saying he wants to marry a mundane, and a parlor maid to boot? Can you see him doing that?”

Sophie’s face twisted. “You don’t know anything,” she said. “You don’t know what he’d do for us—”

“You mean the training?” Tessa was incredulous. “Sophie, really—”

But Sophie, shaking her head, had gathered up her skirts and stalked from the room, letting the door slam shut behind her.

Charlotte, her elbows on the desk in the drawing room, sighed and balled up her fourteenth piece of paper, and tossed it into the fireplace. The fire sparked up for a moment, consuming the paper as it turned black and fell to ashes.

She picked up her pen, dipped it into the inkwell, and began again.

I, Charlotte Mary Branwell, daughter of Nephilim, do hereby and on this date tender my resignation as the director of the London Institute, on behalf of myself and of my husband, Henry Jocelyn Branwell—

“Charlotte?”

Her hand jerked, sending a blot of ink sprawling across the page, ruining her careful lettering. She looked up and saw Henry hovering by the desk, a worried look on his thin, freckled face. She set her pen down. She was conscious, as she always was with Henry and rarely at any other times, of her physical appearance—that her hair was escaping from its chignon, that her dress was not new and had an ink blot on the sleeve, and that her eyes were tired and puffy from weeping.

“What is it, Henry?”

Henry hesitated. “It’s just that I’ve been—Darling, what are you writing?” He came around the desk, glancing over her shoulder. “Charlotte!” He snatched the paper off the desk; though ink had smeared through the letters, enough of what she had written was left for him to get the gist. “Resigning from the Institute? How can you?”

“Better to resign than to have Consul Wayland come in over my head and force me out,” Charlotte said quietly.

“Don’t you mean ‘us’?” Henry looked hurt. “Should I have at least a say in this decision?”

“You’ve never taken an interest in the running of the Institute before. Why would you now?”

Henry looked as if she had slapped him, and it was all Charlotte could do not to get up and put her arms around him and kiss his freckled cheek. She remembered, when she had fallen in love with him, how she had thought he reminded her of an adorable puppy, with his hands just a bit too large for the rest of him, his wide hazel eyes, his eager demeanor. That the mind behind those eyes was as sharp and intelligent as her own was something she had always believed, even when others had laughed at Henry’s eccentricities. She had always thought it would be enough just to be near him always, and love him whether he loved her or not. But that had been before.

“Charlotte,” he said now. “I know why you’re angry with me.”

Her chin jerked up in surprise. Could he truly be that perceptive? Desp

ite her conversation with Brother Enoch, she had thought no one had noticed. She had barely been able to think about it herself, much less how Henry would react when he knew. “You do?”

“I wouldn’t go with you to meet with Woolsey Scott.”

Relief and disappointment warred in Charlotte’s breast. “Henry,” she sighed. “That is hardly—”

“I didn’t realize,” he said. “Sometimes I get so caught up in my ideas. You’ve always known that about me, Lottie.”

Charlotte flushed. He so rarely called her that.

“I would change it if I could. Of all the people in the world, I did think you understood. You know—you know it isn’t just tinkering for me. You know I want to create something that will make the world better, that will make things better for the Nephilim. Just as you do, in directing the Institute. And though I know I will always come second for you—”

“Second for me?” Charlotte’s voice shot up to an incredulous squeak. “You come second for me?”

“It’s all right, Lottie,” Henry said with incredible gentleness. “I knew when you agreed to marry me that it was because you needed to be married to run the Institute, that no one would accept a woman alone in the position of director—”

“Henry.” Charlotte rose to her feet, trembling. “How can you say such terrible things to me?”

Henry looked baffled. “I thought that was just the way it was—”

“Do you think I don’t know why you married me?” Charlotte cried. “Do you think I don’t know about the money your father owed my father, or that my father promised to forgive the debt if you’d marry me? He always wanted a boy, someone to run the Institute after him, and if he couldn’t have that, well, why not pay to marry his unmarriageable daughter—too plain, too headstrong—off to some poor boy who was just doing his duty by his family—”

“CHARLOTTE.” Henry had turned brick red. She had never seen him so angry. “WHAT ON EARTH ARE YOU TALKING ABOUT?”

Charlotte braced herself against the desk. “You know very well,” she said. “It is why you married me, isn’t it?”

The Midnight Heir

The Midnight Heir Son of the Dawn

Son of the Dawn Angels Twice Descending

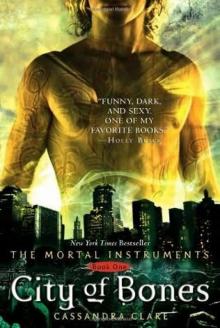

Angels Twice Descending City of Bones

City of Bones Vampires, Scones, and Edmund Herondale

Vampires, Scones, and Edmund Herondale Bitter of Tongue

Bitter of Tongue What Really Happened in Peru

What Really Happened in Peru Shadowhunters and Downworlders

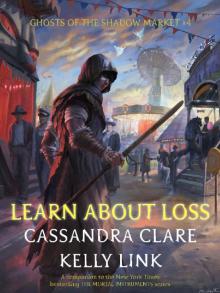

Shadowhunters and Downworlders Learn About Loss

Learn About Loss What to Buy the Shadowhunter Who Has Everything

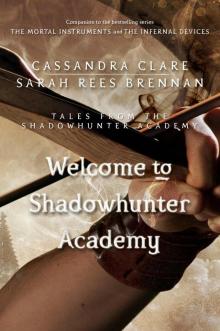

What to Buy the Shadowhunter Who Has Everything Welcome to Shadowhunter Academy

Welcome to Shadowhunter Academy Nothing but Shadows

Nothing but Shadows Clockwork Prince

Clockwork Prince The Fiery Trial

The Fiery Trial City of Glass

City of Glass Clockwork Angel

Clockwork Angel City of Heavenly Fire

City of Heavenly Fire The Rise of the Hotel Dumort

The Rise of the Hotel Dumort The Shadowhunters Codex

The Shadowhunters Codex Cast Long Shadows

Cast Long Shadows City of Lost Souls

City of Lost Souls Lady Midnight

Lady Midnight Lord of Shadows

Lord of Shadows The Whitechapel Fiend

The Whitechapel Fiend City of Fallen Angels

City of Fallen Angels Clockwork Princess

Clockwork Princess Queen of Air and Darkness

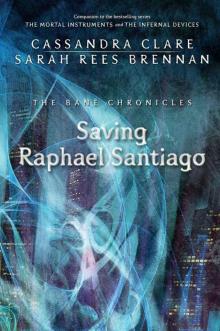

Queen of Air and Darkness Saving Raphael Santiago

Saving Raphael Santiago The Red Scrolls of Magic

The Red Scrolls of Magic City of Ashes

City of Ashes Pale Kings and Princes

Pale Kings and Princes The Runaway Queen

The Runaway Queen The Last Stand of the New York Institute

The Last Stand of the New York Institute A Long Conversation (The Shadowhunter Chronicles)

A Long Conversation (The Shadowhunter Chronicles) The Lost Book of the White

The Lost Book of the White Chain of Gold

Chain of Gold The Fall of the Hotel Dumort

The Fall of the Hotel Dumort Born to Endless Night

Born to Endless Night The Lost Herondale

The Lost Herondale An Illustrated History of Notable Shadowhunters & Denizens of Downworld

An Illustrated History of Notable Shadowhunters & Denizens of Downworld Ghosts of the Shadow Market

Ghosts of the Shadow Market Through Blood, Through Fire

Through Blood, Through Fire Every Exquisite Thing

Every Exquisite Thing City of Fallen Angels mi-4

City of Fallen Angels mi-4 The Land I Lost (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 7)

The Land I Lost (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 7) Queen of Air and Darkness (The Dark Artifices #3)

Queen of Air and Darkness (The Dark Artifices #3) The Wicked Ones (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 6)

The Wicked Ones (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 6) The Wicked Ones

The Wicked Ones A Deeper Love

A Deeper Love City of Fallen Angels (4)

City of Fallen Angels (4) The Evil We Love (Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy Book 5)

The Evil We Love (Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy Book 5) Vampires, Scones, and Edmund Herondale tbc-3

Vampires, Scones, and Edmund Herondale tbc-3 City of Glass mi-3

City of Glass mi-3 Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy

Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy The Infernal Devices Series

The Infernal Devices Series City of Ashes mi-2

City of Ashes mi-2 Cassandra Clare: The Mortal Instruments Series

Cassandra Clare: The Mortal Instruments Series The Bane Chronicles 7: The Fall of the Hotel Dumort

The Bane Chronicles 7: The Fall of the Hotel Dumort The Last Stand of the New York Institute (The Bane Chronicles)

The Last Stand of the New York Institute (The Bane Chronicles) The Land I Lost

The Land I Lost![Saving Raphael Santiago - [Bane Chronicles 06] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/saving_raphael_santiago_-_bane_chronicles_06_preview.jpg) Saving Raphael Santiago - [Bane Chronicles 06]

Saving Raphael Santiago - [Bane Chronicles 06] Clockwork Angel tid-1

Clockwork Angel tid-1 The Runaway Queen tbc-2

The Runaway Queen tbc-2 The Bane Chronicles

The Bane Chronicles City of Lost Souls mi-5

City of Lost Souls mi-5 Every Exquisite Thing (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 3)

Every Exquisite Thing (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 3) Shadowhunter’s Codex

Shadowhunter’s Codex Learn About Loss (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 4)

Learn About Loss (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 4) Welcome to Shadowhunter Academy (Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy Book 1)

Welcome to Shadowhunter Academy (Tales from the Shadowhunter Academy Book 1) Saving Raphael Santiago tbc-6

Saving Raphael Santiago tbc-6 City of Bones mi-1

City of Bones mi-1 Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 1_Son of the Dawn

Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 1_Son of the Dawn Clockwork Princess (Infernal Devices, The)

Clockwork Princess (Infernal Devices, The) Clockwork Prince tid-2

Clockwork Prince tid-2 No Immortal Can Keep a Secret

No Immortal Can Keep a Secret A Deeper Love (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 5)

A Deeper Love (Ghosts of the Shadow Market Book 5) The Course of True Love (and First Dates)

The Course of True Love (and First Dates)